What Shopping Did for American Equality

The Wall Street Journal , December 08, 2022

For Americans, shopping is both a popular pastime and a defining social institution. Our propensity for admiring, coveting, pursuing and accumulating consumer goods has attracted righteous condemnation and knowing satire for well over a century. Shopping, quipped editor J.L. Harbison in 1899, is “an endless hunt for the unattainable, with [the] result of not wanting it when secured.” Yet Americans in his day remained “inveterate shoppers.” We still are.

Nearly 197 million Americans, about 60% of the population, went shopping in-person or online during the five-day period beginning on Thanksgiving, according to the National Retail Federation. The number of in-store shoppers jumped 17% from last year, to 122.7 million. (Many people shopped both in-person and online.) On average, shoppers spent more than $325 on holiday-related purchases.

The urban palaces of early department stores, the climate-controlled corridors of suburban malls, the endlessly scrolling pages of Etsy, the utilitarian aisles of Walmart and the chatty reveals of haul videos aren’t merely sites of envy or exchange. They’re places where Americans—both buyers and sellers—work out who we are and who we want to be. Since the mid-19th century, modern retailing has tested the practical meaning of equality and freedom.

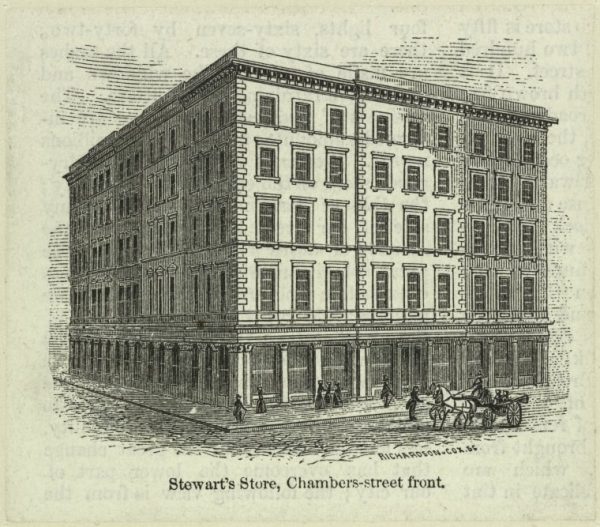

When A.T. Stewart opened his multistory dry goods store in 1846, the Manhattan merchant introduced two revolutionary practices that we now take for granted. He let anyone come and browse freely, whether or not intending to buy, and he charged every customer the same price. Both policies changed the everyday meaning of social equality.

At Stewart’s, wrote a journalist in 1871, “you may gaze upon a million dollars’ worth of goods, and no man will interrupt either your meditation or your admiration.” The store and its many emulators established a new social norm. Any well-behaved patron, regardless of class or ethnicity, could freely examine the merchandise without being pestered or pressured to leave. When Black shoppers today object to being shadowed by clerks, as if suspected of shoplifting, they are voicing expectations of freedom and equality rooted in Stewart’s open-door policy.

Not every retailer embraced the equal right to shop, however, with consequences that reverberate to this day. Fifth Avenue merchants lobbied for New York’s landmark 1916 zoning law, which separated different building uses, because they feared the manufacturing lofts encroaching on their neighborhood. “Their specific concern,” says M. Nolan Gray, author of “Arbitrary Lines,” a history of U.S. zoning law, “is that poor Jewish factory girls are coming to window shop along the corridor on their lunch breaks and when they get off from work, and they’re scaring off their elite clientele.” Keeping out lofts was a stealthy way to limit the freedom of unwanted shoppers, undermining the equal right to admire the merchandise.

Stewart’s fixed-price policy, by making each sale of an item equally profitable, eliminated the assumption that a “good deal” meant a loss on one side of the transaction. With haggling eliminated, salespeople were no longer in the business of taking advantage of customers or vice versa. Stewart fired clerks who misrepresented merchandise quality, and he accepted returns. Sales were expected to be mutually beneficial.

If not adversaries, then, what was the relation between customer and clerk? Were they equals? Or mistress and servant? Countless articles in the early 20th century, from advice columns to first-person journalism, propounded the norm that the “woman behind the counter” deserved the same respect as the woman in front of it. Whatever the difference in social class, shoppers should identify with those who showed them goods. “Observe the same courtesy in asking a service of another as you would expect yourself,” advised etiquette expert Florence Kingsland. Like the Golden Rule it echoes, however, this mutual respect was often an ideal rather than a reality.

The high-handed customer now derided as “Karen” is nothing new, nor are the objections to her behavior. In his 1899 essay, Harbison called out the Karens of the day: “The woman with a Grand Duchess style and manner demands attention, which if not instantly forthcoming results in complaint to the head of the department and often very unjustly leads to the dismissal of a ladylike, obliging and competent assistant.”

Both the sales clerk and her customer represented a new kind of freedom. Urban shopping districts were where women claimed the right to dine outside their homes, walk unescorted and take public transportation without loss of reputation. Thousands of female sales clerks flowed out of stores in the evenings, when downtowns had previously been male territory. Department stores provided ladies’ rooms that gave women places to use the toilet and refresh their hair and clothing. They offered female-friendly tearooms. Directly and indirectly, modern shopping enlarged women’s public role.

It also made sexual harassment a more prominent issue. Men known as “mashers” gathered in shopping districts to ogle and chat up women. Some were no more than well-dressed flirts, violating Victorian norms in ways that few today would find objectionable. Many contented themselves with what an outraged clubwoman termed “merciless glances.” Others followed, catcalled and in some cases fondled women as they strolled between stores, paused to look in windows or waited for trams.

“No other feature of city life offers so many opportunities for making life a burden to the woman who for any reason must go about the city alone or with a woman companion,” opined the Chicago Tribune in 1907, leading a crusade against mashers. Outraged society ladies called for hard labor or public flogging as punishment. “Ogling is just as disgusting and offensive to a good woman as any other mode of attack,” declared the president of the Chicago Women’s Club.

When the Chicago police chief suggested that women avoid harassment by staying home and limiting their time in stores, he was roundly denounced by prominent women, business interests and civic leaders. A clergyman declared it “humiliating…that the authorities responsible for the maintenance of public order should feel themselves compelled to refuse the right of the road to any of the city’s citizens.” Americans increasingly assumed that women deserved the same freedom as men to move about in public—a freedom in which retailers and their suppliers had a large economic stake.

“That a city should be ‘livable’ for unescorted women, and not merely for men, was an unprecedented conception that flourished with Chicago’s retail district,” writes historian Emily Remus in “A Shopper’s Paradise.” “Yet just as novel was the notion that the state had an obligation to establish and maintain that environment.”

By the 1920s, American shoppers were affirming a new kind of equality—the democratization of luxury. Rich and poor couldn’t afford the same products, but they could enjoy versions of the same pleasures. While private transportation had historically been the privilege of the rich, a Model T offered a Sunday drive just as a Rolls-Royce did. By using cheaper materials, ready-to-wear manufacturers sold lower-income shoppers the luxury of owning many stylish garments. The salesgirl or office worker, wrote Samuel Strauss, a critic of the new consumerism, “does not want to look like the millionaire’s wife. She wants to have the pleasure the millionaire’s wife has, the pleasure of living luxuriously.” Installment credit, which became widespread in the 1920s, let customers pay for purchases over time, further expanding access to what were once luxuries.

Taking Stewart’s practices to the next level, F.W. Woolworth built a national chain that until 1934 charged no more than 10 cents for any item, using huge orders and rapid turnover to keep prices low. When Woolworth’s offered a gold ring for 10 cents, it sold 6 million of them in a single year. Instead of relying on sales clerks, Woolworth’s shoppers served themselves, taking their items to cashiers. The chain and its imitators appealed especially to new immigrants and Black Southerners migrating into cities. “Immigrants and Blacks formed a ready market for inexpensive products: china and glassware, ribbons and hair accessories, dolls and mechanical toys,” writes historian Regina Lee Blaszczyk in “American Consumer Society, 1865–2005.” “To these marginalized groups, simple luxuries from the five-and-ten symbolized having accomplished something in the new social order.”

Whether shopping at five-and-dimes, dodging segregation through mail-order purchases, or patronizing department stores, Black Americans found in shopping a measure of respite from social inequality. “Consumption offered material, physical, and psychological satisfaction and comfort. Simply put, it provided African Americans with a taste of the good life,” writes historian Traci Parker in “Department Stores and the Black Freedom Movement.” “Additionally, despite being mistreated and underserved in the retail industry, black consumers learned that their dollars were valued and powerful.”

Yet in the mid-20th century, the restrooms in Southern department stores were still segregated. Fitting rooms and returns were limited to whites only. Black customers couldn’t dine in department store restaurants or sit at dime-store lunch counters. Not everyone’s dollars were equal.

In February 1960, four freshmen at what is now North Carolina A&T University in Greensboro decided to challenge segregation at the downtown Woolworth’s. After buying school supplies, the four young men sat down at the lunch counter, ordered coffee and doughnuts, and declined to leave until they were served. They remained until the store closed.

The students chose Woolworth’s because they found its policies particularly galling. “They tell you to come in: ‘Yes, buy the toothpaste; yes, come in and buy the notebook paper…No, we don’t separate your money in this cash register,’” recalled Franklin McCain, one of the four. “The whole system, of course, was unjust, but that just seemed like insult added to injury.” A whites-only lunch counter violated the promise of modern shopping.

The Greensboro sit-in lasted almost six months, drawing hundreds of participants and counterprotesters and spreading to other downtown stores. Finally in July the store gave in, officially desegregating its lunch counter. Student-led sit-ins swept the South, usually with results that included an end to other anti-Black policies.

“Segregated eateries were emblematic of the profound contradictions of American consumer culture: although situated in the ‘democratic space’ of the department store, they were Jim Crow spaces that reinforced white supremacy and black inferiority,” writes Ms. Parker. “Indeed, such lunch counters may well have become targets for civil-rights protests because they rendered America’s racial contradictions so visible in everyday life.”

For shoppers in the 19th and 20th century, equality accompanied mass production, mass distribution and mass marketing—the same standardized goods for everyone. As Andy Warhol put it, “You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke, and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking.”

Today Coke has fragmented into multiple versions, and restaurant fountains offer customers the chance to mix custom concoctions. To the uniformity of mass consumption, today’s shopping adds a respect for individual differences—a new kind of equality and freedom. Consumer choices embody political convictions, religious values and cultural affiliations. What Americans believe and what they are likely to buy are increasingly aligned, and we’ve only begun to wrestle with what this shift means for how we conceive of equality and freedom. “The endless hunt for the unattainable” isn’t merely a quest for customer satisfaction but for the realization of social ideals. The quest doesn’t end at the sales counter, but it often begins there.