Heard Bad Things About Yik Yak? Try Using It

Bloomberg View , November 13, 2015

Yik Yak is a social-media app that in just two years has become an everyday part of the American college experience. If you’ve heard of it, chances are you think it’s awful. It has a terrible reputation as a dangerous source of vitriol, threats and ethnic slurs -- a reputation only strengthened by recent events.

After protests by black students led to the resignation of the president of the University of Missouri, menacing posts appeared on Yik Yak, which lets people make anonymous, ephemeral notes visible to others within a narrow geographical radius. One of them said, “I’m going to stand my ground tomorrow and shoot every black person I see.”

On Wednesday, police officers in Columbia, Missouri, arrested a man the state university described as “the suspect who posted threats to campus on Yik Yak and other social media.” Later, a student at Northwest Missouri State University was arrested on charges of threatening black students on Yik Yak. (Although Yik Yak posts are anonymous, the company logs users and will share that information with law-enforcement under certain conditions, including imminent threats.)

The stories are typical of those shaping Yik Yak’s media image. Critics, after all, portray it as a clearinghouse of digital hostility. Last month, a coalition of feminist groups asked the Department of Education to force universities to do more to police Yik Yak. They decried it as a tool for “cyber-harassment, intimidation, and threats.” Why would college students embrace such a terrible tool?

I had read about Yik Yak, always negatively, but had never actually experienced it until I was at Princeton last spring, reporting a column on student angst. Students there cited Yik Yak as a way to gauge campus culture, so I signed up and took a look.

What I discovered astonished me.

The Yik Yak I saw came closer to the company’s public-relations aspirations (“home to the casual, relatable, heartfelt, and silly things that connect people with their community”) than to the hate-drenched graffiti its critics had led me to expect. Though largely banal, my samples at Princeton, and later at UCLA and Santa Monica College, revealed Yik Yak posts to be mostly good-natured, often stupid, but rarely evil. At SMC, students typically complain about the parking shortage; at UCLA, they gripe about food; at Princeton they desperately crave sleep. Everywhere they talk about sex.

Most striking is how the anonymity of Yik Yak creates a place of support and solidarity amid academic and social struggles. Shielded by anonymity, students give voice not just to the angry id that attracts condemnation and media notice but to the pain and insecurities they often won’t admit to their friends. This expression can take jocular form, as in the most popular post I saw at Princeton:

Princeton

Where all the kids are smarter than you except the ones assigned to your group project

It can also be considerably darker. “I have everything someone could ever want. And yet I’m still suicidal and always unhappy,” a UCLA student posted. “I feel the same way,” responded another, who added: “:( and then I feel [terrible] for being unhappy because other people have less and are happy so I feel like I shouldn’t complain. I realize that’s not how it works but still :(”. “Me too :(” another chimed in. Publicly confessing such thoughts might get you denounced as a “special snowflake.” In the anonymity of Yik Yak, you can find people who feel your pain and you can at least know you aren’t alone. Maybe that’s why one Princetonian posted, “I yak 10X more when I’m depressed.”

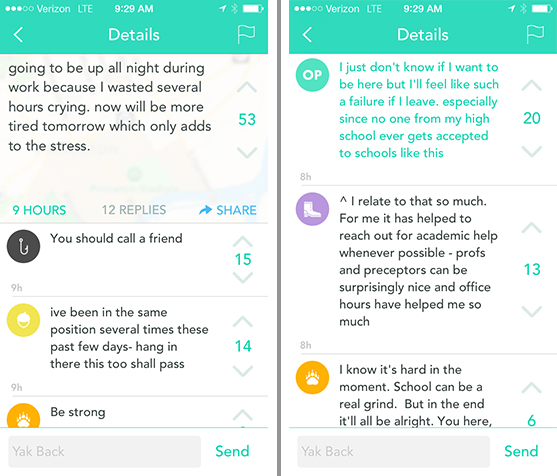

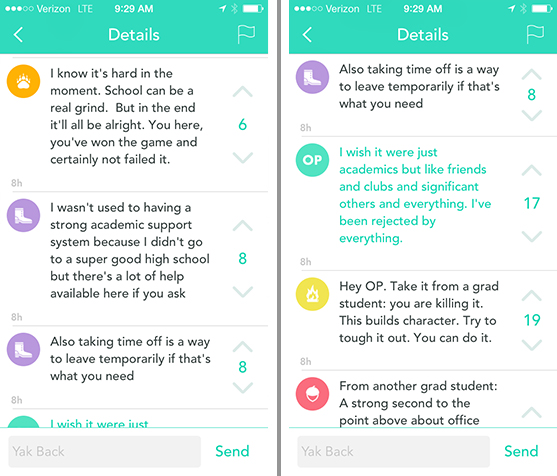

Along with commiseration and encouragement, the solidarity can include practical advice. “I don’t know if I want to be here but I’ll feel like such a failure if I leave. especially since no one from my high school ever gets accepted at schools like this,” wrote a Princeton student. “I relate to that so much,” responded another. “For me it has helped to reach out for academic help whenever possible -- profs and preceptors can be surprisingly nice and office hours have helped me so much.” A couple of self-identified grad students offered encouragement, including reassurance that “most of us love to help you out when we can.”

To students feeling insecure and worthless, Yik Yak carries the message that they matter. Even anonymous strangers care about their well-being. “If people don’t appreciate/value me when I’m alive why should I care that they would care if I died?” wrote a Princeton student. Someone responded, “Hey, my best friend killed himself last year and he kept saying that no one appreciated or valued him but it just wasn’t true. If you really feel that way please go to CPS [the school’s counseling center]. There’s always someone in your life who you mean more to than you’ll ever know.”

So, yes, Yik Yak does attract nasty posts, including the threats in Missouri. But on a routine basis, the app grownups love to demonize is much friendlier than the Twitter and Facebook feeds I read daily. For reasons built into its structure, Yik Yak offers fewer rewards for mean, grouchy, tribal, and polarizing posts and more for those that are supportive, funny, inquisitive, and community-building. Far from encouraging a free-for-all, the terms of service prohibit threats and abuse, as well as “racially or ethnically offensive language.” More immediately, Yik Yak lets users vote comments up or down, giving them longer or shorter lives.

By wielding their voting power, Yik Yak users develop unwritten rules that tend to keep things friendly and fun, observes Briallyn Smith, a graduate student in rehabilitation science at Western University in London, Ontario, who writes frequently on the intersection of technology and college life. “I’ve been amazed by how quickly Yaks that don’t fit the community’s standards will be removed from view -- not by any external moderation, but by the user base,” she writes, noting that “generally you’ll only see negative messages for the first minute after they are posted, after which they are completely down-voted into oblivion.”

This dynamic isn’t an accident. It’s essential to the business. Unlike a website such as Reddit or an Internet-based service such as Twitter, Yik Yak doesn’t draw from the whole world. It can’t survive by attracting a tiny fringe from a huge universe or by aggregating lots of separate tribes. It has to draw most of the potential audience within each local radius, typically a college campus. And everyone sees everything -- no talking only to those who agree. It’s like a small town, but one that people can abandon simply by not logging on. Leaving Yik Yak, unlike other social media, is painless; it won’t hurt you professionally or cut you off from family photos.

If a local Yik Yak provides a place people want to hang out, it will flourish. If it alienates too many users, it will just blow away. The service has spread so fast not because students love to dole out abuse but because they yearn to connect.